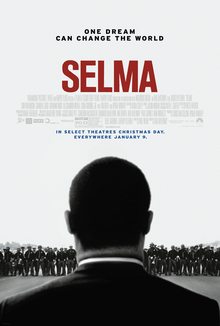

The release of Selma has recently kicked off a minor controversy about the role of LBJ in the events surrounding the historic Civil Rights march. According to the movie, President Johnson is presented as something of a foil for the demonstrators, using the powers of his office to stymie, if not thwart it. In response, several historians, along with former officials in the Johnson administration have registered their objection to this portrayal. One in particular, Joseph Califano, even claims the march was largely Johnson’s idea. Normally such controversies can be reduced to the “truth being somewhere in the middle” synthesis. In this case however, we have two completely different portraits of LBJ which cannot be easily reconciled. On one hand he wants to prevent the Selma March. On the other, he is actively instigating it, the pinnacle of the “outside agitator,” often blamed by Southern officials for stirring up African-Americans against Jim Crow.

I will leave it to the professional historians who have access to the record to settle the debate. Since I have not seen the film yet, I will also pass judgment on the cinematic qualities of LBJ’s role with the movie. For me, there is one idea I feel as qualified as anyone to tackle, the question of how accurate cultural depictions of history need to be. What responsibility, if any, is there towards figures from the past? Even if it were proved conclusively that LBJ assisted with the march, many critics might defend the portrayal of the president as an artistic license, or that historical films can shuffle the deck of established facts to their liking. I think this is a dangerous defense. Plenty of bad history has occurred because of bad history in art, music, literature, and film. One cannot imagine defending the biased portrayal of the South in Gone With the Wind on such grounds.

Of course, every artist has the right to depict the past as they wish, and of course they can also be criticized for the way they choose to do so. Perhaps it is an unfair burden, but the way the past is portrayed in art and popular culture does shape the way we look at history. Often it can even affect the way we see the present. Churchill is said to have once remarked that he learned his English history through Shakespeare’s plays and not textbooks. One might say that Selma is a special case, and that showing LBJ as an antagonist is a small price to pay for having a movie with Black actors and a director released to a wide audience.

In many cases this might be true. 12 Years a Slave was criticized by some for not showing a “good master.” Putting aside Benedict Cumberbatch’s character, who represents about as good a master could realistically be within the confines of the peculiar institution, I don’t think the film or its audience lost anything by not having this figure portrayed. The alleged good master has in fact had his day in the literature of the post-Bellum South. Plus, by showing up in 12 Years a Slave, it would have only weakened the message of the film, creating a distraction. At the end of the day, the good master still owned human beings and participated in their bondage, oppression, and exchange. They were not the ones who brought an end to chattel slavery in America. Therefore, they do not deserve to be resurrected for the present.

However, Lyndon Baines Johnson is a much different case. He was not simply a president uninterested in the Civil Rights movement, or actively working to derail it. Johnson was, for all his complications and problems, a believer in equal rights between black and white Americans. His positions before becoming president aside, by the time of the film he was as firm a supporter of dismantling segregation as anyone in the White House before him. Depicting him as an antagonist of the march does him a disservice and ignores the political cost he was willing to pay for being pro-Civil Rights.

Does Slema need to be a hagiography of Johnson? No. For one very obvious reason, doing so would distract from the march and the bravery associated with it. A Selma dedicated to Johnson would depict him as a white knight coming to save the day, even if it is from those other white knights of the Ku Klux Klan. But turning him into a critic of the march and a foil for Dr. King is irresponsible for two main reasons. The first is that it supports the canard of right-wing revisionists who want to paint the Democratic Party as uniform opponents of Civil Rights in order to promote their idea that because of what Lincoln did, black voters ought to vote Republican (an analysis that ignores the whole Lily White Movement under Taft.). The second is that is robs the viewer of seeing a politician putting principle over politics, which every movement for greater equality needs at some point. LBJ supported the work of King and others and helped pushed the Voting Rights Act through Congress in spite of the possibility of losing the Solid South (a possibility which later became true after the Reagan Revolution).

As I previously stated, Selma does not need to show LBJ as the secret hero of the march. I would further argue it does not need to show or mention LBJ at all. There are enough villains to depict among the local police, CCC, and Klan. I doubt a viewer watching the scenes of carnage on the Edmund Pettus Bridge is wondering where, oh where President Johnson is and what he is doing. Omitting an historical character can be a legitimate move and many historical films and books have used it to reasonable effect, since not every single person involved in an event can be portrayed. Cutting is always required. If accuracy has to be sacrificed to include someone, then it may be better to leave them out rather than engage in contortions of the historical record.

Historical fiction needs to take pains to make sure it does not become a fictional history, especially if doing so serves to provide ammunition for those who seek to do harm in the present. If the facts must be butchered for the sake of producing a work of art, then so be it, yet most films about historical events do not strive for such lofty goals. More often than not, they wish to be educational, at the very least it guarantees a film a permanent shelf life for high school classes when the teacher needs time to catch up on grading. It is important then to try and clarify the kind of responsibility those movies situated between art and documentary have towards figures in the past.

The first principle is this: you do not have to include everybody as a character. Both the very powerful and very ordinary may need to be culled away. For those who are included, not all of them need to be treated as either heroes or villains. Some can simply be characters who help the plot along, like most of us who find themselves in the course of world events. Of those included in the work, if one was a hero in real life, then try to show it in some way. If they cannot be a hero, let them be a character. Do not make them into a villain. In fact, do not make anyone who was not a villain, a villain. At the worst, let them be the comic relief. If someone was a villain, try not to show them as anything else. Certainly do not make them a hero and if their villainy was an especially banal or standard form of evil, then perhaps it is best to leave them out altogether. Even evil deserves an interesting representation.

No comments:

Post a Comment