Tuesday, February 14, 2012

The Adventures of Pizarro Delacroix

Friday, October 21, 2011

Poetry In the Brooklyner and Other News

Hello all, some updates from the very sedate files of Mr. Nardolilli:

I have three poems up in the Brooklyner. Read one of them here, another here, and the last one in this place.

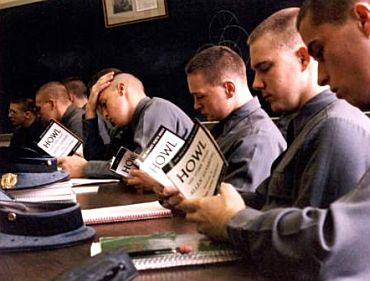

Here's a link to a project centered on the life of little known counterculture figure Shig Murao that presents his life and work. He was the one who was actually arrested for selling Allen Ginsberg's Howl. Unfortunately his role was not depicted in the recent film based on the famous censorship trial, even though he was a defendant along with Lawrence Ferlinghetti (whose last name the spellchecker recognizes, boy is Google Chrome one hep cat!). I reviewed the film when it first came out a year ago. Besides Howl, Shig was involved with City Lights bookstore, the San Francisco renaissance, and was an early zine publisher. In addition he was also a survivor of the Japanese internment and Allen Ginsberg lived out of his closet. A pretty interesting life all around.

Oh, and I was nominated for a Pushcart for a poem in my poetry chapbook.

Saturday, September 25, 2010

Howl: A Movie Review

Except for epics, poems usually don't get movies of their own. The poets are the ones who get the films, though rarely. Eliot and Keats were famous enough to have them. The reasons are simple, most poems do not have stories and are not long enough to sustain a film. Unfortunately, people also do not give the same attention to poetry as they do to prose as well, which means there is less of an in-built audience for an adaptation.

Tuesday, July 13, 2010

“I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by brevity”

I recently read an attempt to create a Howl for my generation. I do not make the allusion myself, the author set it up so, with a single word title meant to juxtaposition with Ginsberg's poem. So comparisons can be made, the point of the poem in the first place. Doing so, one sees that it has its moments but it is no reincarnation, only a parody. However, it was not as good a parody as reading The Waste Land by Orson Welles. "Tweet" does not make it new, as another poet known for his use of homages would say.

I think it may have suffered from the formating of the website. Such a work needs space for the words to breathe. But mostly, it falls flat not in its diagnosing of the problem, but in its referencing. Instead of Ginsberg's use of his friend's adventures and his own intellectual endeavors as a source for an epic, Miller's work reads like a laundry list. It is in need of eyeball kicks and more skillful use in condensing.

These sorts of things have been written before. I remember reading a different one that was about the yuppies. A direction adaptation and twisting worked in this case because it was meant to comment on hos a generation had sold out, or at least refused to carry the flame of challenging assumptions. A Howl for my generation, to be taken seriously, requires a different sort of indignation and rage. It must tell the tale of us not destroying ourselves, but our being witnesses the self-destruction of everything around us. It must deal with how our birthright has been lost. I think it is fitting to consider ourselves a sort of Generation Esau.

Above all, the interesting thing is how Howl, a poem that was as free as any verse could be at the time, has now become its own form. Poems come from it, they have the same structure and make the same stops. A series of expectations is built into the nature of the references, how they are voiced, made, and changed, if indeed they are changed. The process starts right at the beginning. What minds did the author see, and how were they destroyed?